Terry Hirst: The Trailblazer Editorial Cartoonist and Comic Author in Kenya

The Interview Part 2

“The late Terry Hirst was the pioneer editorial cartoonist and comic author in Kenya. In the second part of our exclusive interview with him, talks about his life in Kenya, starting popular publications like JOE Magazine and life beyond the newsroom and editorial cartoons.”

Msanii Kimani: You worked hard around the clock as a teacher, a budding cartoonist trying to build your portfolio etc. in the UK. How did this change and how did you end up in Kenya?

Terry Hirst: It was hard work and then I got the chance to experience what Jomo Kenyatta had described as ‘the freedom that Europe has long forgotten.’ I was invited by the newly independent government in Kenya to head art teacher-training at the Kenyatta College. Kenya had no cadre of professionally trained art teachers for its expanding secondary schools, and the prospect was irresistible, along with the opportunity to set up an entirely new system of purposeful art teacher training, unlike the ‘farce’ of art school. Over the years it proved to be very creatively satisfying, with the first generation of students to graduate producing outstanding work that was featured in the internationally distributed ‘African Arts’ magazine.

Msanii Kimani: Those were lively and very creative years in the country.

Terry Hirst: Creatively, Kenya was a very exciting place to be in 1965, and I soon made contact with the Chemchemi Arts Centre, that had opened up the art scene for the non-formally trained, and then the break-away Paa Ya Paa Art Gallery, where I met some of the most creative minds of the ‘independence’ generation. Elimo and Rebeka Njau, supported mainly by James Kangwana, the late Jonathan Kariara, Charles and Primila Lewis, and Hilary Ng’weno, had established the gallery and I was welcomed to join them, and stimulated to work. I eventually contributed two one-man exhibitions of paintings, which both sold out.

Msanii Kimani: What did you make your foray into the local print media?

Terry Hirst: I had already started to draw as a freelance cartoonist for the ‘Daily Nation’, when Ng’weno invited me to illustrate his regular ‘With a Light Touch’ column, which proved to be very popular. Later, with my third teaching contract ending, Ng’weno and I started one of the first satirical magazines in Africa, called ‘JOE’, after a character in the column. It was an immediate success, and quickly built circulation at home and abroad, but after a year or so, Ng’weno went on to start his prestigious ‘Weekly Review’. Nereas had joined us at ‘JOE’, after leaving Oxford University Press, and we ran the magazine together for the next ten years. I had also been invited to be the first editorial cartoonist in the ‘Daily Nation’, and these years, despite the increasing political repression, are among the happiest, creatively, of my life. At last, I had found ‘the freedoms that Europe had long forgotten’, without becoming a ‘commercial artist’, and doing what I wanted to do from inner necessity. I felt independent and free – I could draw and comment upon anything, and encourage others to do the same – but, of course, in the circumstances of the time it could not last. And it didn’t, as the ‘free press’ came under increasing pressure from political patronage and ‘correctness’, the space in the media environment for pluralist thinking of this sort shrank, and I fell into deep depression, and ‘JOE’ had to finally close its doors.

Msanii Kimani: What a turn of events? Those were difficult times for all. Did other doors open when the “editorial cartoons-one” closed?

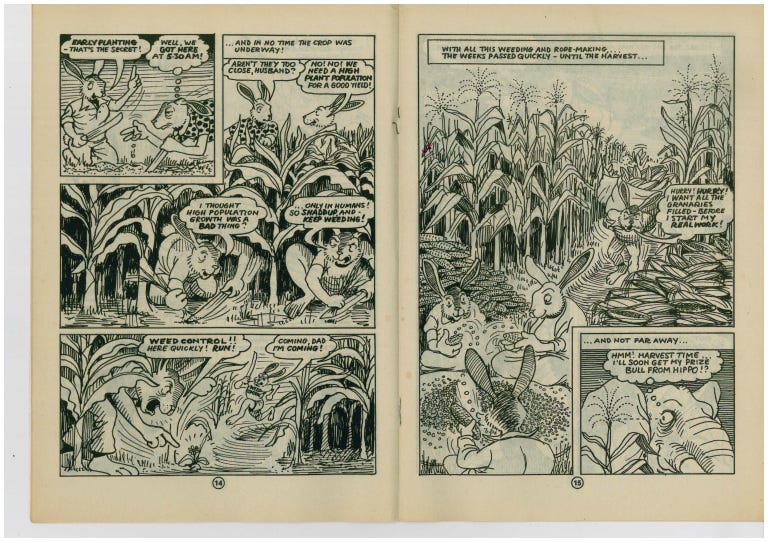

Terry Hirst: But, of course, other doors open, as did “Pichadithi” for a while, and then a whole new market in the field of “development communications.” There were lots of opportunities, and I received commissions from ministries, institutes, NGOs and other donors, in soil conservation and tree planting, immunization and child health, sustainable development and zero-grazing, and information exchanges with children and so on – all of which proved to be very satisfying, and the fieldwork took me to every corner of Kenya, to listen and learn.

Msanii Kimani: The silver lining to otherwise dark clouds.

Terry Hirst: Indeed. Some substantial illustrated books came out of it, like the Kenya Pocket Directory of Trees and Shrubs, (a ‘bestseller’ for Kengo), Agroforestry for Dryland Africa that went all over the world for ICRAF, The Struggle for Nairobi, the story of the creation of an urban environment from scratch, for Mazingira Institute and Rooftops, Canada. There were many more pamphlets, posters and comic books on a wide range of subjects. But, inevitably, the field of development communications became infected with political correctness and inappropriate, if not truly illegal, procurement.

Msanii Kimani: What followed?

Terry Hirst: I moved on to work more closely with Mazingira Institute and my friends— Davinder Lamba and Dianna Lee-Smith, in the growing market for what is called ‘programmed issuing’, as opposed to market publishing. This involved working directly with international foundations and ‘donors’, addressing development communication issues that we mutually agreed. We then found ourselves producing pamphlets, posters, comics, and documentary comic books, which we were then able to distribute free of charge to all primary and secondary schools, colleges and universities, mostly in Kenya, in very large editions of over 150,000 copies, but also often in East Africa and eventually in Africa at large.

Msanii Kimani: What issues did these projects focus on?

Terry Hirst: The issues to be addressed were largely about: shelter and housing; sustainable development; gender and democratic processes – as in the comic for girls called Where the Future Begins!, later published in eleven African countries, and The Seekers of the Secret of Success that was introduced into the Uganda Ministry of Education syllabus; Human Rights in a widely distributed documentary comic, Human and Peoples’ Rights, during the UN’s Decade for Human rights Education— 1995-2005; and on constitutionalism, in a long-running campaign called Designing Our Own Future that started with a documentary comic book, Introducing the Constitution of Kenya in 1998, and continued with posters, wall charts and pamphlets like ‘Civic Education’, 2001, up until, and including the Bomas Conference. This phase of work culminated with the publication of a 54-page documentary comic book on the ideas of Amartya Sen (and personally endorsed by him), targeted at university-level students in East Africa, and called There is a Better Way, adopted and launched at UNEP in 2003.

Msanii Kimani: Which one was the most challenging and why? Which one do you think is the lousiest and why?

Terry Hirst: Probably the Sen book was the most challenging. It is based entirely on his seminal work Development as Freedom, which is a daunting book in itself, despite its astonishing insights and clarity of logic. It took almost a year to finalize my script, working by e-mail with Anantha Duraiappah and the Institute of Sustainable Development, Canada, Flavio Comin and Sen’s office in Cambridge, England, and Davinder, of course, at Mazingira Institute. The actual finished artwork came off quite fluently, and was endorsed by Sen later ‘with warm regards and great appreciation’. The university-level target audience responded well, and they could not get enough copies in Cambridge or Harvard.

Msanii Kimani: That is any artist’s dream. The lousiest?

Terry Hirst: The lousiest? Well, the new art teacher training course that I had introduced at Kenyatta College was bitterly criticized by both the successful international artists, Sam Ntiro at Makerere and Gregory Maloba at Nairobi University, who thought it had departed too far from the British art school ‘model’ they had enjoyed and favoured – the ‘farce’ of training people to be artists, and then expecting them only to teach, whether they have a vocation or not – and it was quickly abandoned after I had left. The British art schools themselves (and the French,) had ‘exploded’ in 1968, and a great deal changed, but little changed in East Africa, where un-trained artists are still looked down upon, despite their frequent success in the market.

Msanii Kimani: That has been a long held perception, battle if you may call it that, pitting those who have gone to school and those who learn on the job. And this determines whether you have work or don’t………

Terry Hirst: There is no such thing as an ‘un-employed’ artist – you are either working at art, or you are not. The difficult bit is making a living: you either enter the market, and become successful – usually with an agent; or you work diligently with your day job, so that you can work on your art when you can; or you become a ‘commercial artist’, and work to order – trying to keep hold of your integrity.

Msanii Kimani: Or you venture into teaching…

Terry Hirst: Teaching without a vocation is misery, and not very effective. Teaching art teachers to teach creative activity to children in a lively and stimulating manner - not just their own skills development - seemed to me the more positive way to go in our circumstances. Skills development for individuals with a gift, is another matter altogether. That can only happen with determination and dedication. Nobody can give it to you, you either have that inner necessity to express yourself – or you don’t. People will choose to live their lives as artists in the ‘gift’ economy whether anyone else intervenes or not. It will happen anyway; the things that have to be communicated cannot be prevented, as Rumi said, it is not that a means has to be found.

Msanii Kimani: Where do you draw inspiration for your work? Who was your role model in the industry?

Terry Hirst: As I said earlier, it mostly comes from an inner necessity to express oneself. In the community and media environment you live in. Creative people – in fact most people – go through three phases to gain this understanding, or ‘tasks to fulfill in our lives’, as Franz Schumacher put it. The first is to learn from society and its traditions, and to find temporary happiness in receiving direction from outside; the second is to interiorize the knowledge gained in the first task – to sift it out, and in the process to come to realize who you are – and in the process to become inner directed; and the third task is to avoid all ego-centric pre-occupations, and cease to be either other directed or inner directed, and achieve creative freedom, or what other cultures call ‘Azad’.

Msanii Kimani: I like that. Important and definitely insightful observations.

Terry Hirst: At this point is where social commissioning really starts to operate, and the work you do is inspired by, not by outside ‘commercial’ vested interests or by personal internal opportunism, but by a genuine desire to offer work for the common good, or what used to be called the commonwealth. It may sound idealistic, but the role models for it exist throughout the history of the graphic arts. I came to realize very early in England that I was part of a very vibrant tradition, in which hundreds of outstanding artists had taken part since the time of Hogarth, but soon came to learn that it existed – quite indigenously – all over the world, so that it is now and integrated cultural global inheritance of human experience in times of continual change. Young artists need to work at their first ‘task’ much harder, and understand where they are coming from.

Msanii Kimani: What is your opinion of the comic industry in the Kenyan and African literary scene?

Terry Hirst: The comic book industry in Kenya has yet to realize anything like it’s full potential, and there are markets in East Africa that are yet to be explored and established, (let alone the export potential) by venture capital and creative investors. Understanding what has been achieved elsewhere remains the key to it for creative spirits in our emerging market economy.

Msanii Kimani: What needs to be done to increase its vibrancy?

Terry Hirst: The publishing industry is still clinging so tight to its founding British colonial ‘model’, and relying too much on printing school textbooks – so you can’t blame the writers in the literary scene. People are persuaded about new ideas when they are moved emotionally in a relaxed manner and agree intellectually, and this opens the door for the graphic artists.

“Comics emotional powers remain under lock and key in all but the most subtle and dedicated hands, and the potential of comics to communicate ideas – maybe their greatest promise – is to date their best kept secret.” Scott McCloud, Reinventing Comics, 2000.

Msanii Kimani: Wise words that are informed by many years of research and practice. Terry Hirst: What do the young creative venturing into market need to do?

Young creative people must ‘learn their songs well before they start singing’, and then do so with focus and dedication. You must have something to show - something that a prospective publisher can see that they can make a profit out of – where you have invested your mind and skills. Don’t wait for people to ask you – do it!

Msanii Kimani: Do you think the industry is able to support an artist to live off it?

Terry Hirst: Put it this way, the field is there waiting to be used and exploited for everyone’s benefit, although, as yet there is no comic book industry in terms of training, publishing and distribution. But it can be fairly quickly established, once the concept is recognized, and artists and venture capital organized. The large media groups and their distribution systems – and preconceived ideas about development – present major obstacles, but even these can be fairly easily overcome with district-based electronic systems, and small local production units, today. Perhaps nobody will make a fortune – but a lot of artists would make a decent living for their families.

Msanii Kimani: Is there hope for it beyond the occasional illustrations in the newspaper?

Terry Hirst: Of course, there is! Forty years ago no newspapers carried graphic art illustrations or cartoons; today they can’t function without them. It is a question of shaping public taste, and the public don’t know what they want until they have tasted it. If it is good, then the marketers will seize on it and ask for more – so, give the marketers something to work on the public with, but don’t get trapped by them! We are talking about establishing markets where none previously existed – it is entrepreneurial and exciting! But, of course, it means a lot of hard work…

Msanii Kimani: What is your opinion of the cartoonists in the newsroom?

Terry Hirst: The marketing department of the Nation group invited me to be the first editorial cartoonist on the Daily Nation and Hirst on Friday become beneficial to the paper, as subsequent surveys showed. But in those days, the newspapers were still working out their relationships with politicians and commerce and it was difficult to always be sure of ‘the party line’ from editorial. At first they even tried to change my captions, without reference to me, until I protested vehemently about independence. In the end we compromised, with me leaving mild ‘joke’ drawings in advance, in case they felt unable, or unwilling, to use the current drawing.

Msanii Kimani: An astitute walk down memory lane………..

Terry Hirst: But nowadays, few editors are willing to let the artist have such complete freedom, although by the looks of it Gado, Maddo, and Kham hold up pretty well, and there is a tradition in journalism that allows left-wing artists to work on right-wing newspapers – if they sell the paper, which they often do. But there is a rethinking going on about the traditional organization of the editorial department that has created ‘a new breed in the menagerie of talent’, as Harold Evans called it as long ago as 1976, and scooped by the marketers under the rubric of ‘convergence’. The new systems of the media cross-fertilize ideas between the verbally gifted and the visually gifted. There are now designer-journalists and journalist-designers, who care about vivid communication, but so far we only usually see such products used in our press from the international agencies, despite all the ‘convergence’ that is supposed to be going on.

Msanii Kimani: Would you say there is a favourable market for comics in the Kenya and Africa in general?

Terry Hirst: Markets are created – not ‘given’. If you have a poor product, people quickly see through it, no matter how well it is marketed. People ‘read’ insincerity or the lack of relevance to their experienced lives. Heart-felt art and commentary, arising from shared community experience, strikes a chord so that it becomes a new necessary ‘need’ in any market economy. You could say, “Make it, and they will come!”

Msanii Kimani: What are the other things that you like doing when you are not working? What are your hobbies etc.?

Terry Hirst: When is an artist not working? I am a voracious reader, and people send me books from all over the world. I enjoy social company, but increasingly I am happily a bit of a ‘loner’, being content to listen and watch – and, of course, think and write. I am writing for my grandchildren in 2020, when they will be able to understand that ‘guka’ would not lie to them about the state we were in, and how it came about.

Msanii Kimani: What are some of the other extraordinary things that have happened to you and also added invaluable experience to your life as an African cartoonist?

Terry Hirst: In a way, everything was extraordinary to me, and always added valuable experience to what I wanted to do. In many parts of Kenya, when I met people who were familiar with my work and enjoyed it, I was always a little amused that they were surprised (and perhaps a little disappointed) that I was a ‘mzungu’ – but we all soon got over it.