Terry Hirst: The Trailblazer Editorial Cartoonist and Comic Author in Kenya

The Interview Part 1

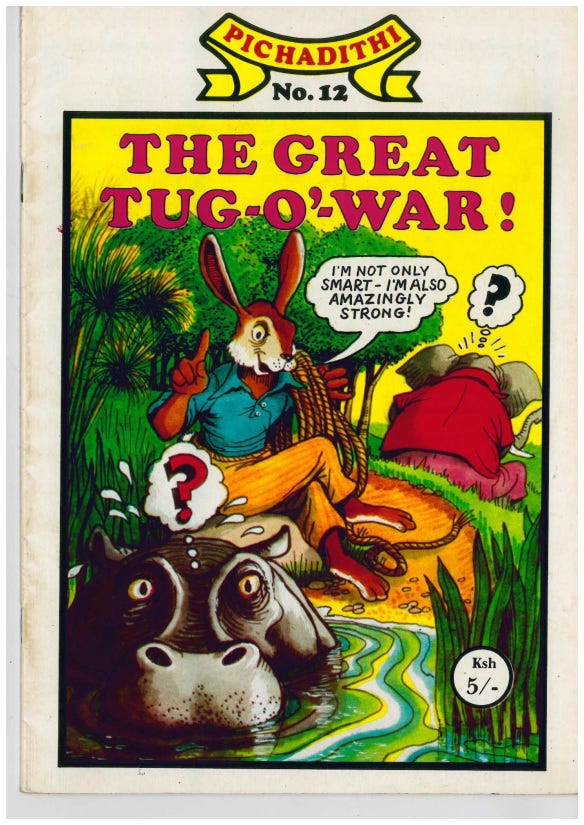

The late Terry Hirst was the pioneer editorial cartoonist and comic author in Kenya. He made his mark with his witty illustrations for the leading daily newspaper and touched the young minds when he created the Pichadithi series. The series title was coined from two Swahili words Picha (pictures), (H)adithi (story) and was without doubt one of the longest published comic series that was also grounded in the African traditional oral literature. The series had over twenty-30-paged comics that were developed from various popular fables, myths and legends that were told in various Kenyan communities and they were a joy for the young readers.

Msanii Kimani: What inspired you to pen the Pichadithi series?

Terry Hirst:It was in 1982, and Kenya had just gone through the trauma of the attempted coup d’état. Working in the mainstream media had become politically very repressive, and I had been forced out of my job as an editorial cartoonist on a national daily shortly before, and my re-appointment as a lecturer in graphics at the university failed to be confirmed in related circumstances. So, I was faced with the usual artist’s problem of how to make a living, which involves taking the products of an artist’s ‘gift economy’ and entering the market economy with them, and for this you really need a patron – or at least an agent.

Msanii Kimani: It must have been difficult.

Terry Hirst: The thing I wanted to do as an artist was to make comic books, but no comic book industry existed in Kenya, and I managed to persuade Kul Graphics, who were very much into the existing markets as pre-press professionals, as well as publishers, that an unexplored market existed that we could both benefit from. In effect, Kul Graphics had become my patron/agent, and would pay me up-front on receiving the completed finished, camera-ready, artwork monthly, thus financing the completion of the next month’s issue. Happily for me, the series was popular from the start, and soon achieved a monthly circulation of over 20,000 copies.

Msanii Kimani: Would you describe it as “more than a comic story series?”

Terry Hirst: For me, with all my troubles, it certainly was – but it was all set in a much larger context. Put it this way, all of Kenya at that time had gone through a violent trauma, as well as the shortages of food, the ‘sunset rice’, the ‘karafu’ and coffee scandals, and the ‘crack-down’ after the coup attempt had been very hard and unrelenting. My wife, Nereas N’gendo, and I both felt that the country – particularly the children – needed ‘healing’, so we thought that traditional stories from all over the country that everyone could relate to culturally, would not only soothe and entertain, but underline the unity of our diversity. Along with that, it also provided the opportunity to provide a well-researched material culture context for the stories that would not have to be explained – but simply ‘seen’ as the way people used to live their lives fully and sustainably. The first title was ‘Kenyatta’s Prophecy’, based upon a traditional story that the founding president had used to explain the struggle for Independence, and the sacrifices that had to be made in order to be where we were.

Msanii Kimani: In the series you were quote saying that “An important part of our African culture is in the traditional stories which have been handed down by word of mouth over the years.” Do you think this has been threatened by the new media?

Terry Hirst: The ‘oral culture’ is alive and well, and, in fact, the new media in the form of the reading of books, re-invigorated it so that it was largely collected by scholars and shared with the new young and the general public. But, with the vast majority of Kenyans still without electricity, we must remember what Okot p’ Bitek told us, that while we talk about the new media and culture, ‘all over the countryside the fires are being lit, and the stories are being told’. The new electronic media, and especially broadband, with its insatiable need for local ‘content’ can only re-inforce this trend – if our creative people are up to it, and recognize that we will always have the attraction of being ‘exotic’ in the international market if we resist the pull of the ‘flat-earthers’, and first build indigenous media markets, alongside the ‘mitumba’ entertainment products we all enjoy. There are ‘niche’ markets all over the world for authentic Kenyan, or East African, creative products, as the musicians are starting to prove.

Msanii Kimani: Why was the series discontinued?

Terry Hirst: I don’t know, to be honest. I had originally been contracted by Kul to do the first ten titles – the first year – which I thought would get me back on my feet, which it did. Then I left the series, and it continued long after that before it went down. My idea with the series originally was to create the beginnings of a sustainable comic book market, in which the graphic artists had full creative control over their work – the choice of theme, the storylines, the finished artwork quality and so on – while receiving adequate recompense in order to live on, and retaining the copyright to their own work. My contract had agreed all this, and I had assumed that the same terms would be offered to everyone else who would then work freelance on the series, that had proved to be very successful. At first it continued well, with talented young artists like the late Frank Odoi and Paul Kalemba doing titles, but then the ‘marketers’ took over, looking for cheaper artists, dictating editorially, and relaxing the graphic art quality standards – so that the artists lost control, and the series went down-hill.

Msanii Kimani: I remember titles likeKenyatta Prophecy, The Greedy Hyena, Wanjiru the Sacrifice, The Amazing Abu Nuwasi, Lwanda Magere, The Ogre’s Daughter, The Adventures of Hare, The Wisdom of Koomenjoe, A Poor Man’s Bowl, Terror in Ngachi Village, The Cunning Squirrel, Omganda’s Treasure, Children of Sango, Simbi the Hunchback etc. How did you source these stories?

Terry Hirst: You see, the ones that you remember include my original ten titles and the early ones of (Frank) Odoi and (Paul) Kalemba, before the artists lost control, and the marketers, reducing internal costs by cutting back on artist’s fees, turned the art products into ‘commodities’ rather than the artist’s ‘gifts’, that they were originally conceived as. But the actual sourcing of stories is not difficult; there are more than two thousand recorded traditional stories in Africa that are easily available! The difficult part is choosing a story that you believe your audience needed to hear, at that time, and shaping it for them so that it will resonate and have larger meaning, as well as entertain.

Msanii Kimani: That is insightful.

Terry Hirst: That’s what the stories were originally about – helping to shape a better you – not just for children, but also for adults. Many graphic artists, through the ages in a widespread tradition, but especially after the industrial revolution and the introduction of market capitalism, have developed, along with the storytellers and the ‘singers of the songs’, a form of ‘social commissioning’ from the communities they live and work among, in tune with their local audiences, and responding to their immediate cares and worries. If local creative people do not do it, the international market will soon move in and take over, largely on the basis of ‘something to tell for something to sell’, and supply that human need to ‘hear the stories’.

Msanii Kimani: Does that meana comic book market especially in Africa is confined to traditional stories?

Terry Hirst: Not quite.A comic book market is by no means confined to traditional stories, of course. It is a vast and expanding field, as even a brief overview of global development of the comic book quickly reveals. I have written extensively about it elsewhere, and hope to set up a kind of ‘Sukumawikipedia’ about it in the near future, called ‘A Brave New Idea – Art for Ordinary Folks! An Overview of Caricaturists, Cartoonists, and Comic Artists, and the Modern Graphic Arts Tradition in the Globalization Process.’ This would enable young artists in our region to quickly see and understand – get the picture – of the universal culture of the medium, and the original social contribution they can individually and independently make by enhancing their own creative skills, and while – if they are any good - sustaining themselves independently and wholesomely.

Msanii Kimani: That would be a gem to nurture the growth of the comic book in the region.

Terry Hirst: The comic book format, this unusual union of literature and art, words and pictures, has contributed a great deal to the social cohesion of those societies in which it has taken root. From the late 1880s it has happened in those societies experiencing the trauma of massive urban/rural migration, that crossover of life styles that has occurred all over the world in the last one hundred years. In fact, no successful industrialized market economy has emerged anywhere in the world, without spawning a comic book industry to assist in the necessary balancing of forces, and the necessary introduction and education of the young into that social process, so that they understand what is expected of them. It has happened in Europe and North America, of course, but also indigenously in China, Japan, and eventually in India, Central and South America, and the Mahgreb, but clearly not yet in Africa South of the Sahara, where in my view it is so obviously needed.

Msanii Kimani: Take me through the journey of your life— When & Where were you born? Are you the eldest or last born? How many are you in the family?

Terry Hirst: Well it has been a long journey, since I was born in Brighton, in England, in 1932, as the eldest in a fairly dysfunctional family that I wouldn’t want to dwell on.

Msanii Kimani: Was it a breeding ground for new talent?

Terry Hirst: Brighton was a lively ‘holiday’ town, and a good place to grow up in, that nestles between the sea and the Downs, with a great deal of natural and public entertainment, good public galleries and libraries, and strong traditions in the theatre and the music hall, so that there was a vibrant social environment outside the primary social environment of the family. These are stimulating seeds for talent, if they fall on fertile ground, although World War II did much to close it all down.

Msanii Kimani: Where did you go to school? What are some of the memorable thoughts of your life while you were growing up?

Terry Hirst: We moved house quite a lot, so I went to many primary schools, until I got a scholarship to Varndean Grammar School, just as World War II was ending, and everything came to life again. I enjoyed a good liberal education, being introduced to literature, art, music, and the humanities, and having some skill in games got to travel fairly widely – if still locally.

Msanii Kimani: What did you want to do in life? Did you always want to be a cartoonist?

Terry Hirst: From quite early on I was sure that I wanted to be an artist. I had a facility for drawing that was well nurtured at grammar school, and it simply never occurred to me to think of being anything else. I used to entertain my friends with drawings, and found that I got great pleasure from it.

Msanii Kimani: What prompted you to choose your career as a cartoonist?

Terry Hirst: An important influence must have been my morning and evening job as a newspaper delivery boy. Everyday, for all the years I was in grammar school, I had a quick glance at all the national daily newspapers in England, and plunged into the graphic arts tradition of the editorial political cartoon, the comic strips and the ‘spot’ cartoons. I didn’t really understand what was happening, but from the 1940s to 1950, I came under the influence of powerful political cartoonists like Low, Zec, Shepard, Illingworth, Lancaster, Cummings, Giles and Vicky – from across the political spectrum– all shaping my thoughts and attitudes. But it still had not occurred to me to be a cartoonist – I wanted to be an artist.

Msanii Kimani: Where did you go to college? How was it? What are some the challenges and trials that you encountered while trying to learn the trade?

Terry Hirst: I chose to go to Brighton College of Art, much to the annoyance of my headmaster, who liked to visit his former pupils in Oxbridge, and have never regretted it. Brighton attracted a host of well-known artists as visiting lecturers – people like Mervyn Peake, an outstanding draughtsman, and Woodford, a famous sculptor– since it was near to London. The specialist courses were broad and wide, and we could ‘taste’ everything, and in the cafes, night-clubs, jazz-clubs, music-halls, cinema clubs and theatres of the city, with fellow art-students, we could argue all night to make sense of it all.

Msanii Kimani: That must have been fun. A vibrant environment no doubt!

Terry Hirst: They were exciting years, training to be an artist. But there was, and still is, a catch! There is what John Berger calls ‘a tragic farce in English art schools’ – in fact it is in most art schools of the world – and this concerns the prospect of ‘making a living’, in an age when patrons no longer exist. The easiest option is to become a teacher, and the best artists get jobs in art schools, and ‘teach artists to teach artists, to teach artists!’ and hope to continue with their creative work – like my own visiting lecturers. The less well connected or able become secondary school art teachers, and slowly come to terms with the fact that they are too emotionally exhausted to do their own work at the end of a day. But it is possible, while difficult, and the media provide the option for graphic artists. Being an artist in the public media is largely self-elective – anybody can see if you are any good – you just have to prove it with the ideas and drawings.

Msanii Kimani: That sounds like there were limited choices. Were there any dangers to an artist who made any of these choices?

Terry Hirst: There are dangers in this for the graphic artist, because once you enter the market system all the pressures are upon you to become an entirely ‘commercial artist’ – as it used to be called – selling your skills to produce ‘commodities’ that other people decide are sellable. I had a friend at college, whose father used to draw two ‘double spreads’ per week for national comics called ‘Film Fun’ and ‘Radio Fun’, year in and year out. (He swore that the office boy wrote the scripts!) They lived decently, and the dad only worked in the mornings and went horse-racing almost every afternoon, but it wasn’t a life that attracted me.

Msanii Kimani: Please give me an outline of the body of your works- the things that you have done- both in Africa and internationally.

Terry Hirst: After graduating as an artist and a teacher, and completing my National Service in the army – where I taught–, I got a job teaching in Crawley New Town, that offered housing, clinics, and schools for my children, and was near to London. I started to build my portfolio of work, and approached a lively local newspaper to secure a regular weekly front-page ‘spot’ cartoon, commenting on local governance and so on. It proved to be popular, and I was invited to do a similar ‘spot’ for a nearby East Grinstead paper. Working just on the weekends, I started to get stand-alone cartoons and features into national magazines.

Msanii Kimani: That was without doubt a good start.

Terry Hirst: It certainly was exciting. On the teaching front, I was appointed Head of Art at one of the largest comprehensive schools in England, in Nottingham, but I continued with my freelance work in the national media, becoming a regular weekly cartoonist in the ‘Tribune’, and doing features for the ‘Times Educational Supplement’, along with cartoons for ‘Twentieth Century’, ‘Peace News’ and similar publications. But it was a heavy load; school teaching, teaching evening classes at the Nottingham School of Art and the WEA, along with my private practice – all to keep my head above water and pay my mortgage and install central heating, while trying to get up the courage to ‘go solo’ with my artwork in a very competitive market.

Beautiful interview. I loved his work!

Msanii, A forum dedicated to African literature in these uncertain times is just what our children need to understand their origins...

I am looking for some copies in the Pichadithi series( Wanjiru the Sacrifice, The greedy Hyena and The Amazing Abunuwasi) to replace to the ones that did not survive our juvenile years.

Kindly advice where I can find them, Thanks