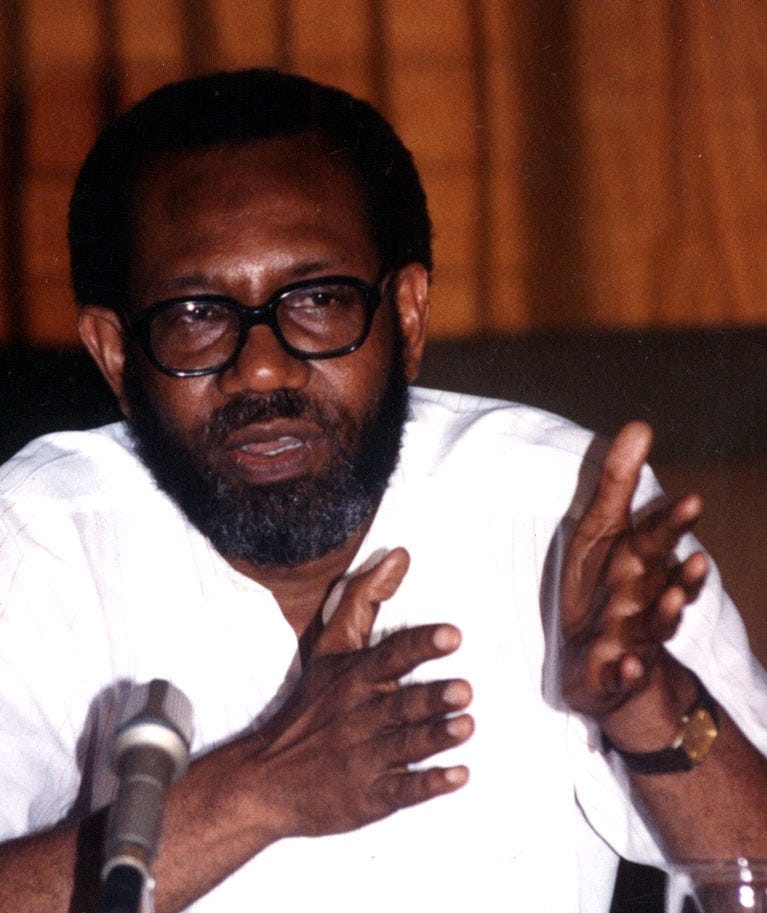

Poet in Politics: Exclusive Interview with Abdilatif Abdalla

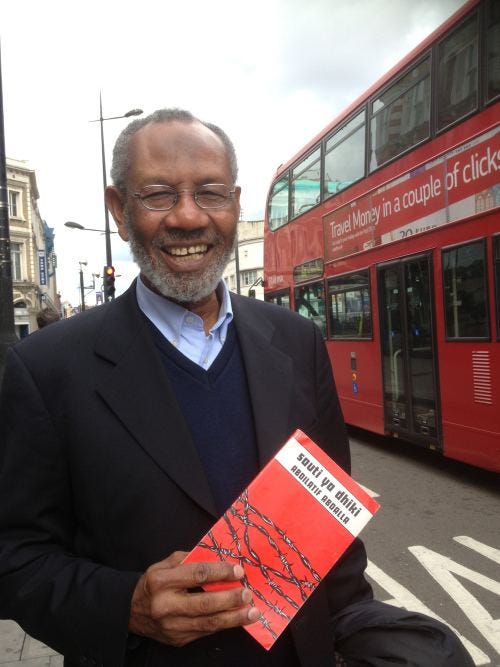

Thoughts on Kenya Twendapi? and the writing of Sauti ya Dhiki while in Prison

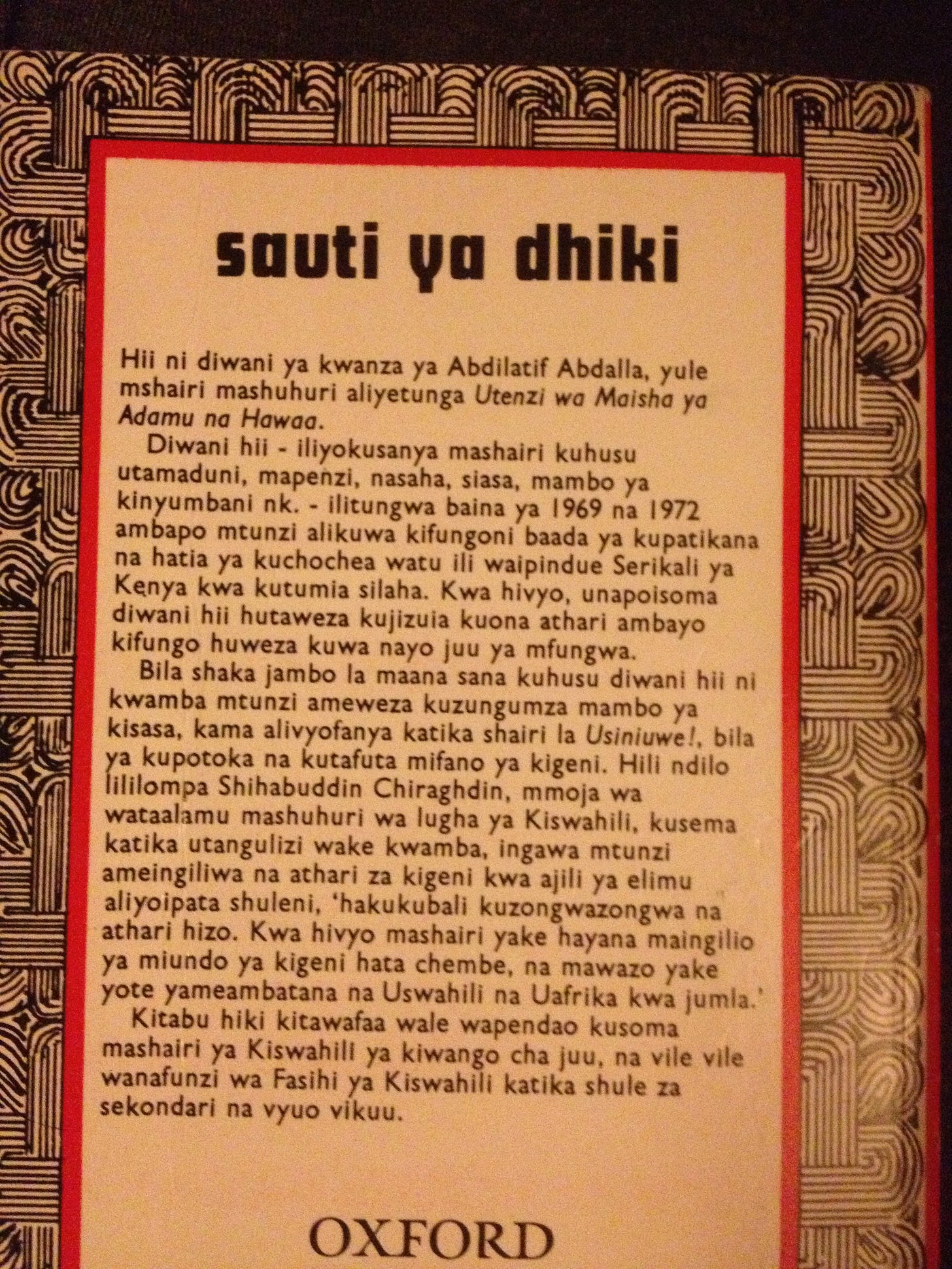

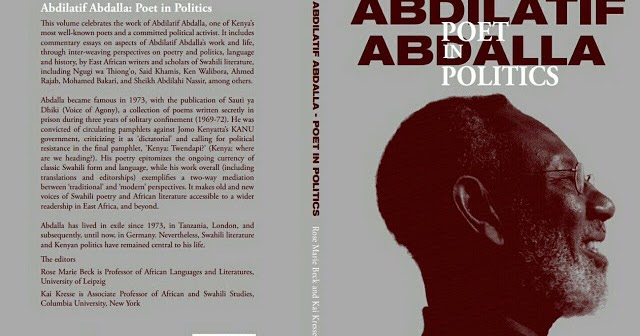

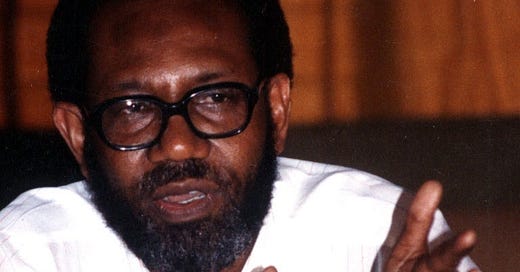

Professor Abdilatif Abdalla was imprisoned by the late President Jomo Kenyatta’s regime after he, in a political pamphlet Kenya: Twendapi? (Kenya: Where Are We Heading To?) criticised the President on the direction the country was headed. While in prison, he wrote an anthology of poems that ironically won the 1974 edition of the Jomo Kenyatta Award for Literature, an award named after the very man who had imprisoned. Msanii Kimani wa Wanjiru interviewed him.

Kimani: Prison literature forms an important body of art in Kenya and Africa in general. Would you describe it as more than mere writing or do you feel they represent anything?

Abdilatif: I think it is more than just writing. Because by writing, such writers- especially those who were imprisoned because of their writing, and while in prison were denied writing materials- are at the same time defying the powers that be and making a very bold statement that there is no way that they can be stopped from expressing their views through writing. In other words, by doing so they continue to resist against the very system, which imprisoned and restricted them.

Kimani: Kenya has its own generous share of literary material authored behind bars.What are your thoughts?

Abdilatif: The prison writings in Kenya, which I am aware of are direct responses to the different political situations in which our country found itself. For example, during the colonial period we had works such as 'Mau Mau' Detainee, by JM Kariuki, which, although was not written in prison, did, nevertheless, mainly dwell on the experiences which the author went through from 1953 to 1960 while he was detained by the British colonial government for being a member of the Mau Mau movement. Another one is Mau Mau Author in Detention: An Author's Detention Diary by Gakaara wa Wanjau. This was originally written in Gikuyu. As the sub-title indicates, this was a diary the author secretly wrote and kept, recording his experiences in different detention camps in Kenya where he was detained for a total of eight years between 1952 and 1960 as a result of his activities in the Mau Mau movement. Another one which is in the same league is Freedom Fighter,by J. Nyamweya. And there are several others.

The post-independence period gave us prison works like Sauti ya Dhiki, Ngugi wa Thiong'o's Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary and the novel, Devil on the Cross; Alamin Mazrui's anthology of poems, ChembechaMoyo, which he wrote when he was detained without trial for more than two years in different Kenyan prisons after his play, Kilio cha Haki (Cry for Justice) was performed at the University of Nairobi; also Maina wa Kinyatti's Kenya: Prison Notebook and Mother Kenya:Letters From Prison, 1982-1988, both written during his six years' imprisonment, to mention but a few.

One of the intentions and expectations of the jailer is to kill the spirit of the one jailed because of his convictions - especially if those convictions are political. But for the one who strongly holds on to them, prison or detention can never break such a person, but, I dare say, does quite the opposite. Because that which fire cannot burn only makes it harder. And this is manifested in these prison writings wherein you can see how stronger that prisoner or detainee has become and how more convinced he is and more committed to what he believes in, compared to before that person was jailed or detained.

Here we have mostly concerned ourselves with those writings which were written within the walls of prisons. But, I think, it is also important to bear in mind that even those works which were written outside the confines of prison cells, but in an environment which was equally oppressive (in a wider prison, so to speak), should also be given a very serious consideration.

Kimani: The late Wahome Mutahi noted that "For many writers writing about their horrid experiences behind bars is often cathartic, therapeutic, if you may call it.” Do you feel the same?

Abdilatif: I quite agree with Mutahi's observations. At least from my personal experience, one of the things which helped me to keep my sanity in the solitary confinement which I was in throughout the period of my incarceration at Shimo La Tewa Prison and Kamiti Maximum Security Prison, between December 1968 and March 1972, was my writing. My poems gave me company; and, in the process, we communicated with each other and, sometimes, argued with each other! Solitary confinement, as the term itself denotes, is a very lonely kind of life; in fact it has within it elements of mental torture, which are partly designed to break you and kill your resistance and spirit. Composing my poems was one the three major things which sustained me.

Kimani: You were imprisoned for 3-years and put in solitary confinement. What was going on in your mind as you penned the poems?

Abdilatif: As I mentioned earlier, writing those poems gave me sustenance, strength and the will to endure what I went through in prison. One of the very valuable things which solitary confinement gave me was the space (however tiny my cell was) and time (plenty of it since I was not allowed even to work, despite the fact that I continuously begged the prison authorities to allow me to do so) for reflection and stock taking. It enabled me to test myself as far as my political convictions and beliefs were concerned. I sometimes jokingly say that I thank the Government that imprisoned me for having given me that opportunity to test my convictions.

Therefore, in Sauti ya Dhiki one can find poems in which I keep on reawakening and reaffirming- again and again - my political convictions; also there are political poems which deal with the situation Kenya and Africa were in at that particular time; what I was mentally busy with - sometimes grappling with near uncertainties and doubts; my very personal and emotional feelings, such as longing and worries for the family members I left behind, as well as the torments of loneliness and boredom, which kept reminding me that they will never desert me. There are also poems which deal with matters cultural. Equally, what also occupied my mind was unceasingly thinking about how, once I am out of the prison gates, I will continue with the struggle to bring about meaningful changes in our country.

This exercise of composing my poems was comforting to me, but at the same time it was a dangerous undertaking, because in the process I was breaking prison rules and regulations which governed my solitary confinement. One of the restrictions, among many, was not to be allowed any reading or writing material. In other words, I was forbidden to write or read. I must tell you, that was very painful to me - especially the very cruel rule of not being allowed to read, since from the time I could read I have always been very fond indeed of reading whatever I could lay my hands on. Therefore, that restriction was like passing a death sentence to me!

So, for the first six months or so of my imprisonment I had absolutely nothing to read! It was after those very long six months, and after several times insistently requesting the Kamiti Senior Superintendent of Prison - whenever he paid me his regular visits to check if the rules of my confinement are duly followed by the prison warders guarding me- to allow me to have something to read, was I finally allowed to have a copy of the Koran, but- and he emphasized on that- only the Arabic version, and not in translation. Little did he know that by allowing me to have only that Arabic version of the Koran he was handing me a very powerful instrument, which helped me a lot in soothing my internal pains and sufferings as well as strengthening my inner resolve even more! Or, maybe, he did know the power of the contents therein, otherwise he would not have insisted that it should not be in translation, thinking that I would not understand it in Arabic. Because in it I met characters in Islamic history, who were tortured to death and others harassed in various ways so that they denounce their newly-found faith, but they never relented; others who were lured to a better life if they would abandon Islam, but they preferred their poor lives in dignity and with their faith intact rather than wealth in humiliation; others who preferred imprisonment rather than “freedom” under subjugation and dictation; and many other similar situations. So, that particular copy of the Koran was more than enough for me. I did not need to request for anything else! However, it was after so many months that I was allowed to have a Kiswahili translation.

Kimani: How did you get started?

Abdilatif: The acquisition of writing material was to come after about another six months. It was almost one year since my arrest in December 1968 that I managed to persuade one of my regular prison guards - who had turned to be sympathetic to me because of my politics - to get me a small piece of pencil. God knows how I treasured that! That, together with my weekly ration of rough toilet paper, which proved to be very useful as writing paper!

Kimani: That must have fired the creative juices in you. How were the first steps like?

Abdilatif: Being in possession of these two very important and valuable materials, I was now ready to start my poetical exploration within the solitary confines of the four walls of my cell at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison. I wrote my very first poem in prison, titled Nshishiyelo ni Lilo! (I Hold Fast to What I Believe In) in September 1969. This particular poem was a sort of a letter to my elder brother, Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir, although at that time I did not have any possibility of sending it to him, because I was not allowed neither to receive nor send letters, even to my immediate family. My brother was the main person who was responsible of my politicization during my teens, and I had promised him that I will never surrender even when I find myself in trouble with the Government. I also kept a diary in a coded language, and wrote a short novel called "Ni Haki Yangu". After my release, I did not bother to put the finishing touches on the novel. I just lost interest in it.

Kimani: Ironically, the anthology of poems won you the 1974 edition of the Jomo Kenyatta Award for Literature, an award named after the very man who had imprisoned you.Did you find this ironical?

Abdilatif: Many people, and on many occasions, have asked me that very question. Yes, it sounds ironical. And sometimes it makes me feel uncomfortable to be associated with an Award which bears the name of the person whom I strongly feel had betrayed Kenya as a whole, and betrayed me personally. I say he betrayed me personally, because since the days when I was in primary school, when Kenya was still under British colonial rule, I used to regard Mzee Jomo Kenyatta as one of my heroes. For example, during those days the school day started with all the pupils assembling at the school courtyard and singing the British anthem, "God Save the Queen", before they entered their respective classrooms. I remember how when I was attending primary school in a village called Takaungu I used to secretly and whisperingly substitute the word "Queen" with "Kenyatta" because I believed that he deserved that prayer more due to the fact that he was fighting for the rights of our country and its people. (There was only one student friend who knew about this "subversive and seditious" act of mine and, thank God, he never betrayed me to the school authorities).

Now, when I answer this question I always emphasize that although that Award was named after Kenyatta, he had nothing else to do with it. This Award was the brainchild of Kenya Publishers Association, which also made the money for the Award available. How it came that Sauti ya Dhiki came to win it, or who the judges who decided so were/is still a mystery to me.

I say he betrayed me personally, because since the days when I was in primary school, when Kenya was still under British colonial rule, I used to regard Mzee Jomo Kenyatta as one of my heroes. For example, during those days the school day started with all the pupils assembling at the school courtyard and singing the British anthem, "God Save the Queen", before they entered their respective classrooms. I remember how when I was attending primary school in a village called Takaungu I used to secretly and whisperingly substitute the word "Queen" with "Kenyatta" because I believed that he deserved that prayer more due to the fact that he was fighting for the rights of our country and its people.

Kimani: What are the circumstances that prompted you to publish Kenya: Twendapi? (Kenya: Where Are We Heading To?)

Abdilatif: Kenya: Twendapi? was the seventh in the series of occasional pamphlets I used to write, in consultation and cooperation with my political comrades, and which were clandestinely distributed. They were signed "Wasiotosheka." This was the term which the first President, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, used in his public rallies to refer to us who were not satisfied with the situation in the country and who were opposed to the way the country was being governed. That is, we were "the disgruntled" or "the dissidents", as the government used to call us.

Now, allow me, please, to put the reason of writing and distributing this pamphlet into context. When this pamphlet was written I was 22 years old. But from the age of 19 years I was a member of the then opposition party, Kenya Peoples Union (popularly known as KPU), which was led by Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. At that time, I had just started my second year as an Accounts Clerk at the Municipal Council of Mombasa.

KPU was legally formed and registered by the government as a political party in 1966. As you will see, this was just three years after Kenya attained its independence. The formation of KPU was necessitated by the fact that about two years after independence some of those who were in power (and it was a very powerful and very ruthless small group) had already started to divert from the path which Kenyans had charted during the independence struggle, and which was enshrined in the KANU Manifesto of 1963, which was a relatively radical document. Greed, which was manifested by this group through the amassing of wealth, mostly by foul and unjust means, and the unashamedly grabbing of land by the ruling class, was already in full swing. The rot had already set in. The government had also started to be intolerant of any opposing views, and did not want to listen even to its own members of government who saw things differently, and who offered suggestions on how things should be put right and, in the process, return to the path agreed upon while fighting for independence. In short, this group was very arrogant and was behaving very badly indeed. They behaved as if the country was their personal property, and they did not have any qualms whatsoever!

Some of those who did not agree with the situation we then had in the country were the then country's first Vice President, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who was also the Minister for Internal Affairs. Others were Bildad Kaggia, who had by then already resigned as an Assistant Minister of Education (but remained in KANU) because of his disagreement with the Government's policies, especially regarding the land issue; Achieng Oneko, then Minister of Information, and Tom Okello Odongo, then an Assistant Minister for Finance, to name but a few, and several other nationalist figures. These patriots, when they saw that things were starting to go wrong, they first tried to change things from within. But after a while they realised that they were not - and will not - get anywhere. Hence the formation of KPU as the alternative.

When these patriots left the government and the ruling party, KANU, to join KPU, the regime rushed a new law through parliament, which was subsequently passed. This new law made it mandatory for any sitting Member of Parliament who resigned from the party which made it possible for him or her to be elected as an MP, to seek re-election. As a result, all those who "crossed the floor," to use the parliamentary jargon, had to go back to their respective electorate to seek new mandate. The real purpose for the Government to introduce this law was to threaten and stop other KANU Members of Parliament who also wanted to join KPU from doing so. In the ensuing by-elections (which were dubbed by the media as "the little general election)," – and despite the restrictions placed by the Government in order to make KPU’s campaign near impossible, KPU garnered nine seats.

Within a short period, KPU became popular with the ordinary masses across the country. But there were also pockets of resistance against it among some elites in some communities, especially from the Central Province, but also from other areas. This opposition, in my opinion, stemmed mainly from two factors: The first one was due to independence euphoria: the argument which gained currency was that the government was only three years old and, therefore, some people were of the opinion that it was too early to paint it with a negative brush. They felt that it should be given more time to find its bearings. I vividly remember the difficulties some of us had during those days when trying to persuade such people that if things were not nibbed in the bud there and then, once this beast of a government grows fat and stronger, it would overwhelm all of us and make it more difficult to bring about the required changes.

The second factor was based on this cancer which continues to eat and destroy the very body of our country, namely what Koigi wa Wamwere rightly calls "negative ethnicity.” This "negative ethnicity" was nurtured and perpetuated after independence, mainly by those who wielded the reins of power. And, as is apparent today all over the continent of Africa, the genesis of "negative ethnicity" is the unequal distribution of the national wealth and resources. Jomo Kenyatta and his cabal were masters of this deadly game. It is no secret that certain selected communities benefitted from this at the great expense of the big majority of other Kenyans. Therefore, those who were beneficiaries of this unfair system were hostile to KPU, whose policies were based on social justice.

This "negative ethnicity" was nurtured and perpetuated after independence, mainly by those who wielded the reins of power. And, as is apparent today all over the continent of Africa, the genesis of "negative ethnicity" is the unequal distribution of the national wealth and resources.

When KPU's support among the Kenyan masses grew stronger, all the government's radars read "danger"! It subsequently started to restrict its activities and harass and detain its leaders and its prominent supporters. And the Government's naked intolerance and repression against KPU was to become more evident during the Local Government Elections, which took place in August 1968. In those elections, KPU fielded candidates across the country. In all, there were about 1,800 KPU candidates. Definitely, this was going to be the first big opportunity to electorally test the popularity or otherwise of these two sides: the ruling party, KANU, on one side and the first opposition party in independent Kenya, KPU.

But for some months before, there had already been indications that the Government had become unpopular among the people. The signs were clearly on the wall for all to see: that the government would lose these Local Government Elections. And the KANU Government didn't have the courage to let the Kenyan people exercise their constitutional right to choose between the two sides. What it instead did was to instruct the retuning officers all over the country to disqualify all the KPU nomination papers. And, you know, what was the reason given by the Government for those disqualifications? That all the KPU nomination papers were not correctly filled in!! Not even a single one? Now, this reason could not be accepted even by the silliest of persons. In my opinion, the seeds of dictatorship in Kenya, which came to devour the very soul of this country for so many years after, were sown during that period.

Something had to be done against this very dangerous tendency. At the very least to speak out against it. So I made it the topic of the next pamphlet, Kenya: Twendapi? In short, in it I argued- and I must admit - in a very angry and fiery language, that by behaving the way it did, the Government had robbed the Kenyan people their constitutional right of peacefully and democratically electing their leaders. I also said that if it behaved in the same dictatorial manner in the 1970 General Elections, then the only alternative for the people of Kenya would be to rise up and remove the Government by force!

Kimani: Did you share the content of the article with your family members before you published it?

Abdilatif: I remember showing my elder brother and mentor I mentioned earlier, the draft of the pamphlet, Kenya: Twendapi? His comment was that the tone and the diction used was very harsh, and he advised me to tone down the language. My stubbornness took the hold of me and I declined to do so. I was so angry with the Government's intransigence and dictatorial and arrogant behaviour that I did not want to dilute the expression of how I really felt.

Kimani: You have since published other works. What are they?

Abdilatif: Some of the publications that I have churned out include Utenzi wa Maisha ya Adamu na Hawaa (an epic poem on the life of Adam and Eve), (Ed.) Utenzi wa Fumo Liyongo by Muhammad Kijumwa, Wema Hawajazaliwa(Ayi Kwei Armah’s novel, The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born), co-compiler and co-editor of Liyongo Songs: Poems Attributed to Fumo Liyongo.

Kimani: Which one was the most challenging and why?

Abdilatif: I can easily say that I regard Sauti ya Dhiki to be my most challenging and rewarding work. Challenging because of the circumstances in which it was written, as well as the opinions and feelings expressed therein. Rewarding because of the way it was received by the reading public, and continues to be received even though 36 years have now passed since it was first published. There isn’t any which I regard as the lousiest.

Kimani: Where do you draw inspiration for your works of art?

Abdilatif: My inspiration comes mainly from the surroundings and the environment I am in. My main influence and role model as far as my poetry is concerned, are the two people I mentioned earlier, namely my great uncle, Ahmad Basheikh (who used to give me his poems to read before he went to recite them at Sauti ya Mvita, the radio station which existed in Mombasa till mid-1960s), and my elder brother, Ahmad Nassir bin Juma Bhalo, who is a major Kiswahili poet. I was also very much influenced by the poetry of the 19th century Mombasa poet, Muyaka bin Haji, who lived between 1776 and 1840.

Kimani: What are the other things that you like doing when you are not working? What are your hobbies etc.?

Abdilatif: Reading is my most favourite hobby. Then comes listening to good music, and going to classical music or jazz concerts. I also like travelling to new places.

This is enlightening and liberating. I have just figured out I have been missing great texts. I need to revisit the libraries and bookshops.

Very informative. Now we know more about the writer of Sauti Ya Dhiki and political atmosphere that sent him to prison where he produced this and other manuscripts. Kudos.